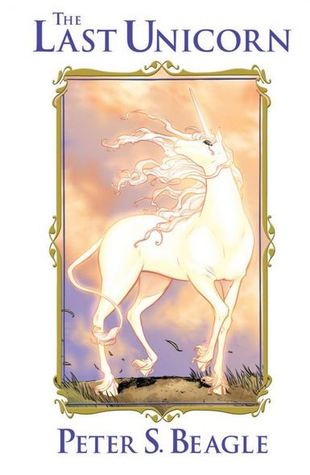

Like most people my age, my introduction to Peter S. Beagle’s beloved classic fantasy The Last Unicorn was the 1982 animated film (for which Beagle wrote the screenplay, thank goodness) that I first pulled off a Blockbuster shelf above my head because of the brilliant unicorn on the cover. When I was a child, modern unicorns were generally fluffy beasts with glitter in their manes, colored in pinks and rainbows and frolicking around clouds and butterflies. This unicorn was clearly engaged in some epic battle with a frankly Satanic-looking, burning red bull, and despite knowing nothing else, I was convinced it was going to be awesome.

I was not wrong about any of this, and so began my lifelong obsession with The Last Unicorn. Like children do, I watched the thing I loved over and over until I had memorized the lines and the words to all of the songs by the folksy, mostly-forgotten band “America.” And then I read other unicorn books, better unicorn books that appreciated the same majesty and inherent otherworldliness and melancholy of an immortal beauty like The Last Unicorn. And then in middle school, I finally had my own copy of the film on DVD. And then I finally found a copy of the book in the high school library, and it blew my mind, how much bigger the story was, how much more complex and clever, and I fell in love a second time. And then when I had graduated college and was getting around by myself in New York City as a twenty-something near-adult, I went to the legendary Strand bookstore for the first time and bought myself one book, my own copy of The Last Unicorn, at long last. I planned to see—by myself, if necessary!—a special theatre showing of the film/author talk in D.C., where Beagle himself would talk about the story and the film, and author talks always do signings (the film tour itself was cancelled, so not all dreams are meant to be).

Well. All this is to say that I know The Last Unicorn very well, so I was quite excited to learn that there would be a graphic novel adaptation in 2011. I couldn’t manage to find it for a while, but I recently had the opportunity to finally read it, and I feel I’m in a good position to review it as to how it stacks up against the original novel and the film.

As expected of an adaptation, the graphic novel follows the book closely in plot, characterization, and narrative voice, though the film’s influence is clear in the art direction and the splendidly elegant and detailed illustrations. I was pleased to see that many memorable story events that the film entirely skips made it into this version, including Hagsgate, the wizard Nikos, and the princess calling to the unicorn, a decision which allows the graphic novel to better showcase the surprising cheek and intricacy of Beagle’s world-building than even the lovely film. Beautiful, powerful illustrations work together with direct descriptions and dialogue from the novel to capture a true sense of Beagle’s original, tenderly piercing voice and observations that illuminate the story’s themes on people, beauty, and stories themselves.

But, just like the film is no substitute for Beagle’s original novel, this graphic version cannot be truly enjoyed or understood without prior knowledge of The Last Unicorn from the book or film.

I do not mean to say that the graphic novel is not good. Most of the book is excellent, with the aforementioned weaving of original text and lovely new art, the delightful inclusion of all major events, and the skillful depiction of the world. Both the fanciful and frightening pages are laid out with equal skill for action and atmosphere to create the right amount of tension and wonder. There are a few abrupt transitions here and there, but overall it rolls along quite beautifully until it trips into one of the most important parts of the story, the highest section of the rising action, and proceeds to sprint and stumble drunkenly through the whole chapter.

This part of the review necessarily contains spoilers for those who are not familiar with the story of The Last Unicorn. To avoid them, skip to the tenth paragraph.

Chapter 5 contains the whole portion of the events in King Haggard’s castle, from the introduction of the unicorn’s human shape as Lady Amalthea to entering the Red Bull’s lair. Numerous major developments key to the plot and the story’s meaning as a whole occur in this section. We see the unicorn lose herself in Amalthea’s humanity and understand the threat of the unicorn’s growing mortality, we learn King Haggard’s motivation for stealing the unicorns and discover that the unicorns are trapped in the sea, we have the struggle to reach the Red Bull, we witness Prince Lir’s growth into a hero, and, of course, we watch Prince Lir and Amalthea falling in love. This section of the novel does so much to build, explore, and illuminate the story’s themes and ideas, that Beagle’s story wouldn’t have the same feeling or power without it, and it is really worthwhile to slow down and take your time reading it. The love story itself, for instance, is inextricably tied to Amalthea’s crisis of identity and being as she learns the suffering and joy of a finite life. The reader needs to absorb both conflicts as they grow together to appreciate how they play into the ideas of beauty, finite time and immortality, what life is, and what stories do and why they work in certain ways.

Until this chapter, the novel kept a fairly steady pace that matched the progression of the action. For example, a whole issue was reserved for Mommy Fortuna’s carnival, and another for the events with Captain Cully and the introduction of dear Molly Grue. It lingered over exquisite moments and made sure to highlight characterizing details and actions. In comparison, the castle chapter feels rushed and poorly planned, as though the creators at IDW Publishing had no idea how much content they would need to cover before they got there and decided to cram in as much Beagle text as possible to make up for cutting or skimming certain details. Some of the creative decisions make sense, like cutting King Haggard’s men-at-arms as Beagle did for the film’s screenplay, but the page design and severe condensing of content sets a breakneck pace for this chapter that belies opportunities for meaningful character development or reflection on the significance of the chapter’s events.

A significant chunk of the chapter, for example, is portrayed through a series of spreads that set two characters opposite each other, one on each page, with a scene or more told through the panels between them. Presumably, each end of the spread is meant to be told from that character’s perspective, but the panels therein never seem particularly personalized to the character in departure from the omniscient narrator, and the connection suggested between them rarely adds insight. It is a creative, artistic design that might have worked well when used rarely or if applied to scenes that would benefit from speed and summary rather than time for atmosphere. But, used so liberally, the device becomes transparent, and the story suffers from broken transitions, knowledge leaps, and dramatic dialogue or illustrations falling flat because of a sense that the comic is rushing to “get to the good bit” with the bull fight.

For a graphic novel that has otherwise been quite faithful and attentive to Beagle’s original story, we lose much of the tale’s power and complexity from the reductions and pacing in this chapter. There is a powerful scene in the story in which King Haggard rebukes Amalthea for forgetting herself as a unicorn and becoming human, and in the same conversation we receive the marvelous revelation that the unicorns are trapped in the sea. However, the accompanying illustration for this discovery is remarkably underwhelming compared to the novel and film, with a small illustration of unicorns in seafoam in the corner of a spread while Haggard and Amalthea talk, and then the transition between when the king leaves and Schemendrick calls Amalthea to see the talking skull is so quick and abrupt that I thought two pages had stuck together. Haggard threatens the unicorn like a proper comic book villain, but there is no lingering on his unhappiness or his obsessive, possessive madness and joy like in Beagle’s screenplay, something that I felt failed his characterization and detracted from the magnitude of Amalthea’s quest, that the unicorns were another prize for a dissatisfied conqueror than the only success in a powerful, disappointed, and selfish man’s quest to wring his share of joy from life.

As another example, Prince Lir mkes an earlier appearance in the comic before we know who he is, just as he does in the original novel, as a bored prince reading a magazine, but though he performs heroic deeds for Amalthea’s favor and attempts to write poetry, we do not get to see him grow from a “sleepy fool” into a true hero and good king as we do in the novel; his transformation occurs between one page and the next. We never truly get to know him as a character beyond his love for Amalthea. The love story itself is rushed and blossoms between one page and the next—a common problem for many adaptations and stories, but at least the film had that no-fail magic of an animated love song to indicate the passage of courting and developing understanding and affection. This impacts the power of Amalthea’s conflict of identity, too, as we barely get a glimpse of her misery and confusion in a mortal body before she discovers the happiness and beauty a mortal life can hold through her love with Lir (something the film also accomplished with a song, but then Beagle was very fond of songs in the novel).

Here finish the spoilers. Read on without fear.

Knowing all of these things from the book and film, I may turn a more critical eye on this chapter than the unfamiliar reader would, but this is what I mean by being unable to “truly” enjoy or understand The Last Unicorn from this graphic novel alone: you would simply miss too much of the consciousness, voltage, sadness, and charm contained in this important section of the story. Granted, the loss or change of meaning must be expected to some extent when a written story is converted into a graphic novel, because the illustrations, the selection of text, and, in this case, the constraints of six issues, must inevitably alter the voice, the story’s visible priorities, or the pacing.

However, I still consider this a good adaptation of the story. The next and final chapter returns to the previous four chapters’ excellent pacing and attention to detail for the climax of the unicorn’s quest and the conclusion of the story, and I was quite happy with the ending. Most of the story’s original flavor is conveyed through the many memorable “Beagle-ism” lines that make up the text and carry the major themes through the novel, so I was never in doubt that I was visiting The Last Unicorn again. I enjoyed visiting the characters again, and I am always happy to see one of my favorite stories given the full illustrated treatment. It was fun to read. Nothing earth-shattering compared to my understanding of the original novel, but the art was lovely, and, despite technical difficulties in Haggard’s castle, this adaptation gave enough detail and care to paying homage to the original book that I could feel the love for the story in it, and I was genuinely excited to turn the page and see how they portrayed the next scene or stunning moment.

Fans of The Last Unicorn should expect a slight watering down of the original novel as they would for practically any adaptation, but they will enjoy seeing Beagle’s words and the unicorn’s quest brought to life in elegant and exciting illustrations. I elected to borrow the book from the library for convenience, but I would not object to having it on my shelf, and it is worth picking up for fun and the enjoyable experience of revisiting the story in a more modern incarnation. New readers will probably enjoy the graphic novel more than I did as a magical adventure with flawed, likable characters, interestingly odd quest events, and more cheek than is typical for a literary medieval fantasy comic, with clever observations about stories and people and the enchanting, unusual decision to make a unicorn the protagonist. But you won’t know what you’re missing, so I personally suggest reading the book first or making a plan for it soon after.

Glad to see such a classic story continue to live on.

LikeLike